So, I moved outside the city and found a good reason to get some kind of moped as an alternative to biking. As age has passed by 40+ years, this of course must be a non-ordinary ride. Why not get a classic Swedish cargo moped (tricycle with bed in front), change tho motor to a modern 4-stroke to gain some power?

Not sure why, but I got attracted to electric alternatives. A few models have been sold in Sweden over the years. At least two domestic companies have existed, nowadays it is probably only Chinese imports. One of these companies, TransportEL built very heavy-duty mopeds. I started out looking for a used one and finally found one for a decent price.

With low price comes the need for maintenance. The moped had been left in high grass for a couple of years resulting in unnecessary rust on the hot-dip galvanized frame. The brakes were stuck, all electronics oxidized and the batteries were shot. The latter may seem like a bummer, new high-quality lead-acid batteries are not cheap, but I was planning for a battery conversion.

Model and History

Before diving into the restoration work, I want to provide a brief history of these cargo mopeds.

The moped was built by the Swedish company TransportEL in Västerås. The company went bankrupt a couple of years ago but has emerged again, selling spare parts and reselling refurbished cargo mopeds. They were kind enough to send me some spare part lists and provide me with the model year of my moped (2003).

My specific moped was sold to the Swedish mail distribution company Posten (PostNord nowadays). Mopeds were used by some mailmen in more populated areas. They were equipped with a large box arrangement on the cargo bed. The bed is larger than usual (1200×1000 mm) and the color is the light yellow that Posten used around this time.

I have been unable to find any photos of these mopeds, only ones with two-stroke gas motors and electric ones from another Swedish company (Norsjö). The photo of the latter may give an idea of what my moped looked like.

Another feature from the mail delivery usage is the gas pedal. That’s right, this moped doesn’t have a gas handle but a pedal on the right side. Strange but quite comfortable. It also lacks any brake handles on the bar, only a pedal that actuates both the front and rear brakes.

Forward/reverse is selected with a switch on the left handle. On the same handle, there is switches for turn signal, horn and lights on (there is no high beam).

The design has evolved over the years, the first ones having suspension on the rear wheel. At some point, this was replaced with a spring-suspended drivers seat.

All models seems to be built somewhat like Meccano. A sturdy tube frame with simple sheeting to cover moving parts. Most parts in this Meccano are existing third-party components. This includes things like lights, motor controller, charger, switches and so on.

The drive train consist of an electrical motor, a Curtis speed controller and gear reduction. The motor is directly coupled to the rear wheel. The Curtis controller doesn’t have any regeneration. Drive train voltage is 24 VDC. The motor is a 1,5 kW Italian-made motor speced for continuous drive, speed is 3000 rpm.

Reducing the motor speed is done in two steps. First a reduction using HTD-8M timing belt and gears, then a second reduction on the chain drive. The drive is using a sturdy double-width (06B-2) chain with double-toothed gears. The reason for this in unclear, I’d say an ordinary motorcycle chain would handle the torque from the moderate-powered motor.

All wheels are equipped with disc brakes. The calipers almost seems custom made in milled aluminum. A caliper from an existing common moped would have been cheaper.

Earlier models didn’t have a galvanized tube chassis, something I find a great feat on my model.

Photos found in the wild shows that the layout of the electronics box has changed over the years. Some models had the headlight mounted externally, while my moped has the light integrated in the box.

Except for the drive train, all electrics on the moped is 12 VDC. The voltages is derived from a DC-DC converter. The chassis is not grounded and 24 V and 12 V ground are separated.

Verifying the Drive Train

First out was a test of the electrical parts. Did the motor even run? With the old batteries dried out, I used a tiny LiPo pack to just power the electrical system. The reason not using a power supply was the current draw. Peak current draw turning the motor was far higher than any 24 VDC PSU I have at hand.

With power connected, some things worked fine. I drew a rough schematics to get a better understanding of connections, fuses, etc. The moped uses two separate voltages, 24 V and 12 V and the chassis is not connected to ground. The 24 V is only for the drive train so everything related to the drive train such as motor controller, safety switches, etc.

The 12 V system is fed by a DC/DC step-down converter and supplies lights, turn signals, the horn and so on.

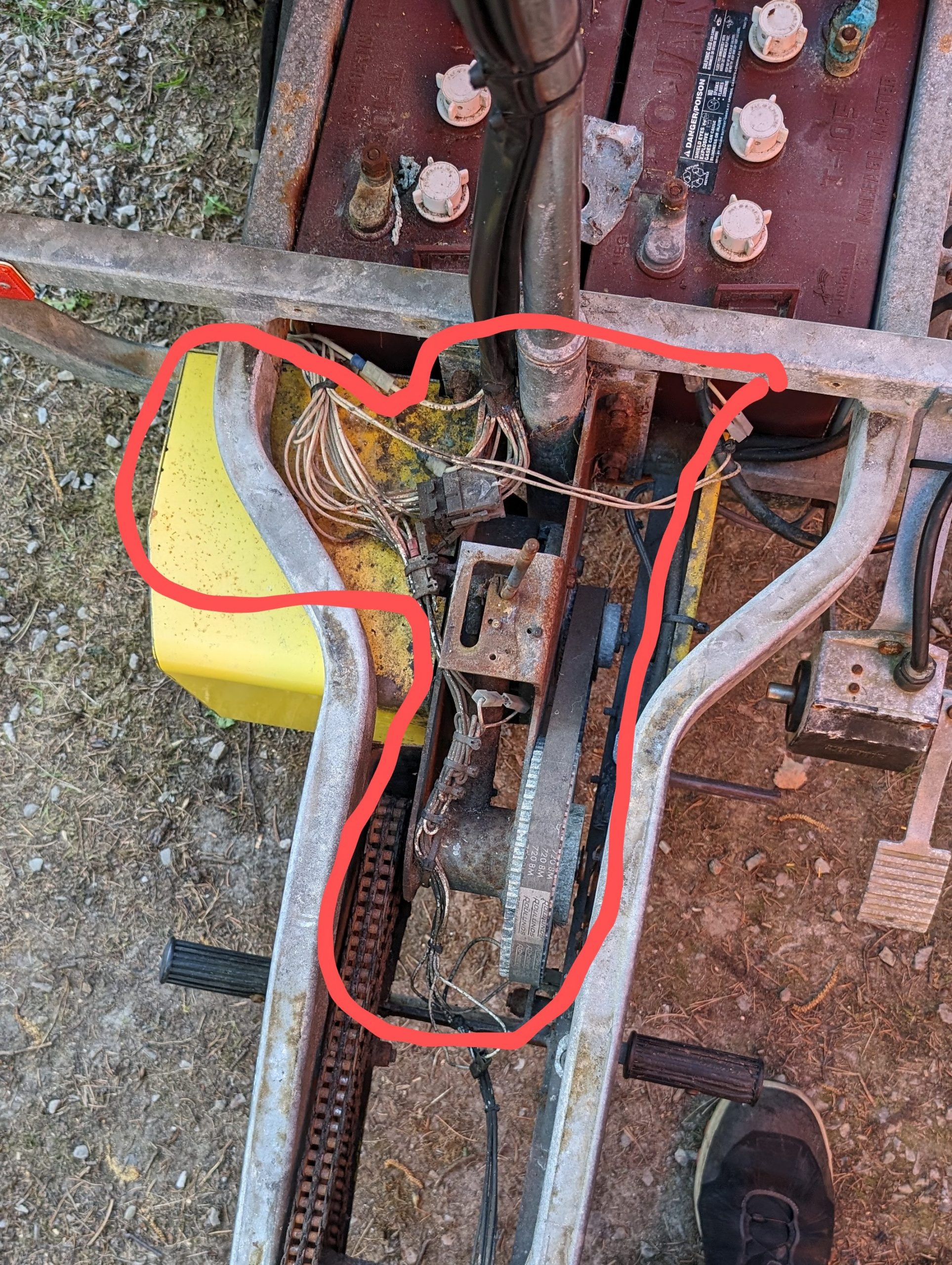

With power applied, I could conclude that most things didn’t work. Lights were intermittent and I the motor didn’t run. Using my rough schematics, it was possible to track down problems with micro switches connected in series as safety switches for the drive train. Just shorting these switches actually got the motor jumping to life!

Unfortunately it was running very intermittent. I feared problems with the motor or the controller and it took some troubleshooting to understand that the cause was in the control signal to the controller.

The motor speed is controlled by a pedal (yes, a pedal not a handle) with a 5 kΩ potentiometer. The cable seal at the top of the pedal box was bad and weather had done it’s job on the inside. A temporary potentiometer and some alligator clips did the job, I got the motor running good enough to ride the moped for a few meters.

So the conclusion was, drive train working but electrics in general need an overhaul. Let’s get going!

Cleanup

First out was a general cleaning and removing of rust from the old battery compartment. The rust was removed mechanically with wire brushes and chemically using phosphoric acid. The bare metal was then protected with spray-on zinc paint.

Everything was washed and the compartment around the chain was cleaned from old oil and grease. The chain and the small drive sprocket was found to be in bad shape and will need to be replaced.

Unfortunately, the life outdoors have resulted in even galvanized parts being rusty. Nothing major but still annoying. Nothing to do about that for now.

New Battery

Because the moped is missing it’s power source, a new battery solutions had to be arranged. As mentioned, the plan was to replace heavy lead-acid batteries with some modern lithium-based batteries. After reading up on current tech and scanning the market for used EV cells I decided to go with new LiFePO4 cells. These are nice drop-in replacements for lead-acid cells, 8 LiFePO4 cells would end up at about the same voltages as the old 4×6 V lead ones.

As a bonus, using Lithium-based cells results in quite a weight-loss. The old lead batteries weighted in at 120 kg, the new pack at around 20 kg!

Modern battery cells needs a battery management system (BMS) to handle cell balancing and protection Seemed like the newer models from JK-BMS were good, being able to handle cell balancing also during discharge. In the back of my head, there is an idea of upgrading the moped battery from 24 V to at least 48 V to handle some kind of motor upgrade. Because of this, a BMS supporting 16 cells and a high current draw of 200A (that would be almost 10 kW nominal, with even higher peaks).

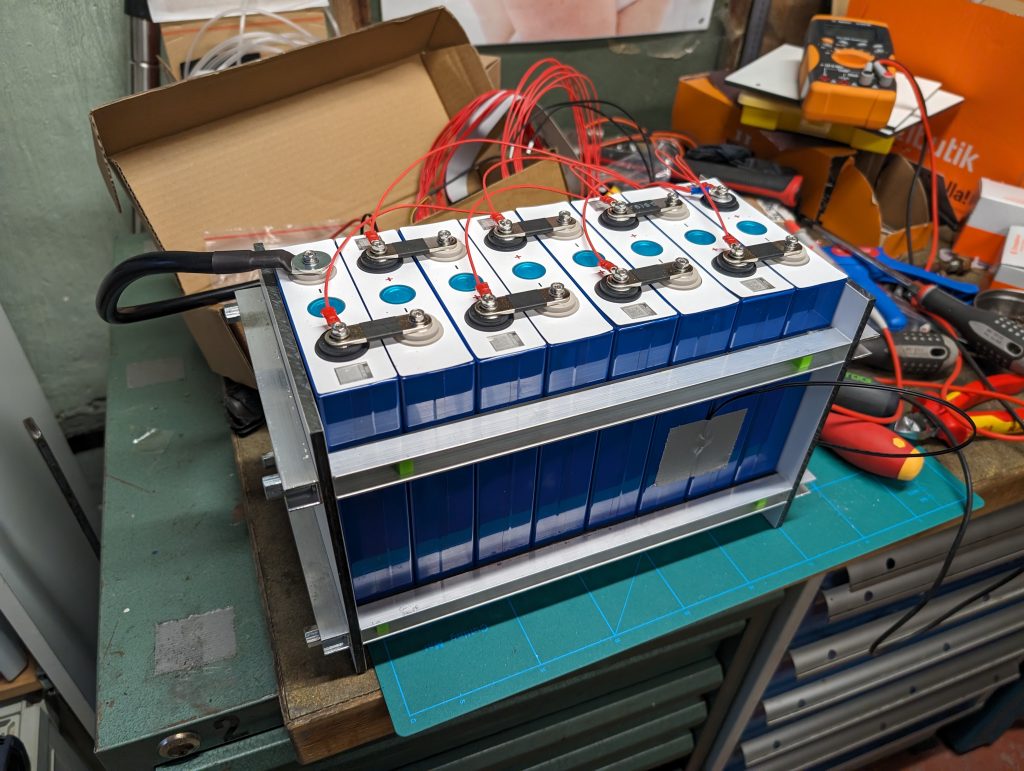

Cells were ordered and assembled into a pack with compression. There is quite some info on cell compression available with many different opinions on the benefits. I just concluded that it probably is good to keep the cells flat and in place. This was done with some laminate plates, extruded aluminum struts and threaded rods. I placed thin fiberglass plates between the cells to avoid any risk of short circuit due to vibrations.

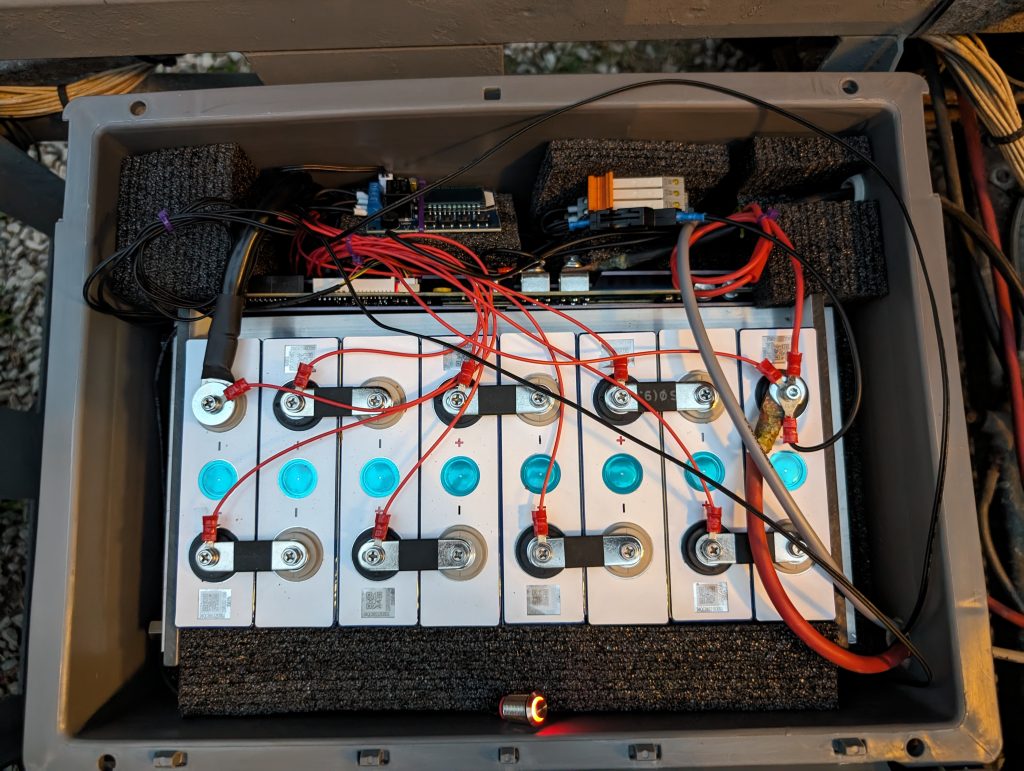

Next problem to solve was how to protect the cells from weather. I had an idea of welding a metal box but wanted to get the battery done. Ended up ordering a plastic container and just mounted things in cut-out foam.

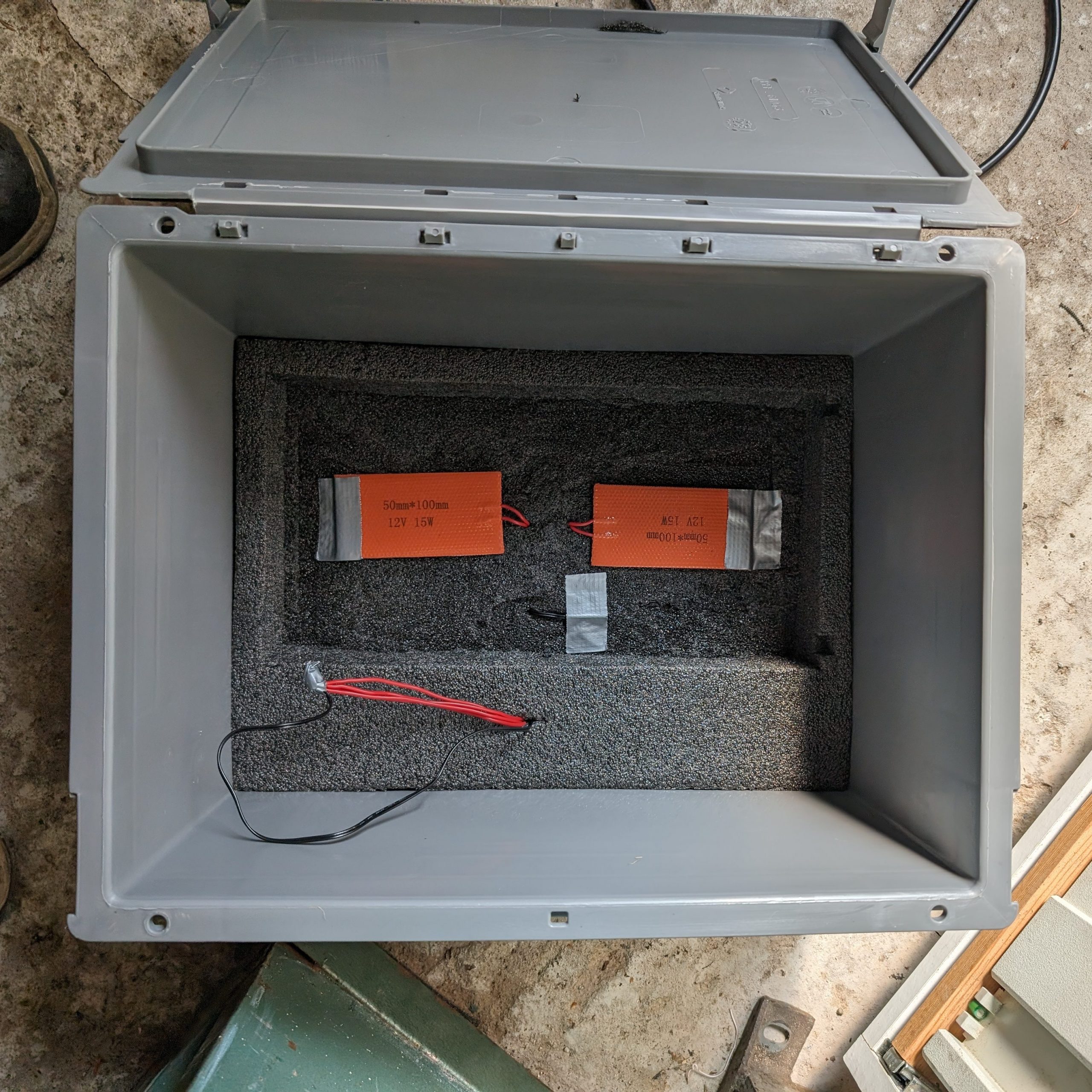

I placed silicone heat mats under the battery pack and did some power routing through relays to be able to heat up the batteries in the future. The setup will be able to heat the batteries during charging if the temperature is below 0 °C. This is a requirement for LiFePO4 cells to avoid damage. The setup should allow for external control of the heating so it can be turned on during discharge to improve performance.

Charger

The moped featured a built-in battery charger. This means, it was already equipped with a 230 VAC inlet (which needed to be replaced due to being cracked). The old charger was a simple lead-acid battery charger with a huge transformer. Stripping this saved quite some kilograms.

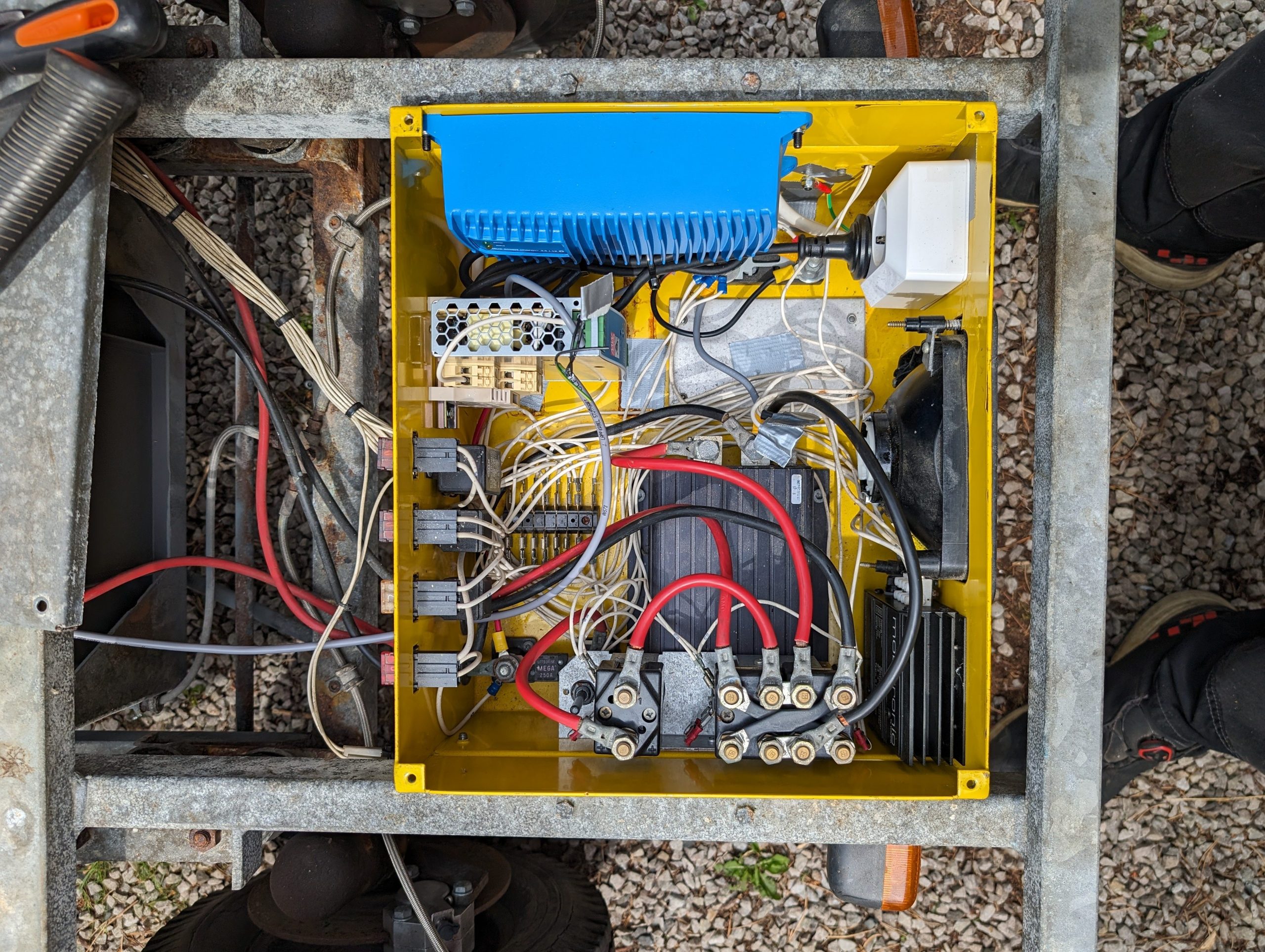

LiFePO4 batteries requires matching chargers. I don’t really trust cheap stuff so I went for a nice charger from Victron. Expensive but well-built, with water protection and a useful statistics available over Bluetooth. I mounted the charger in the electronics box on the moped together with a 24 VDC power supply to power the battery heaters in the winter.

Brakes

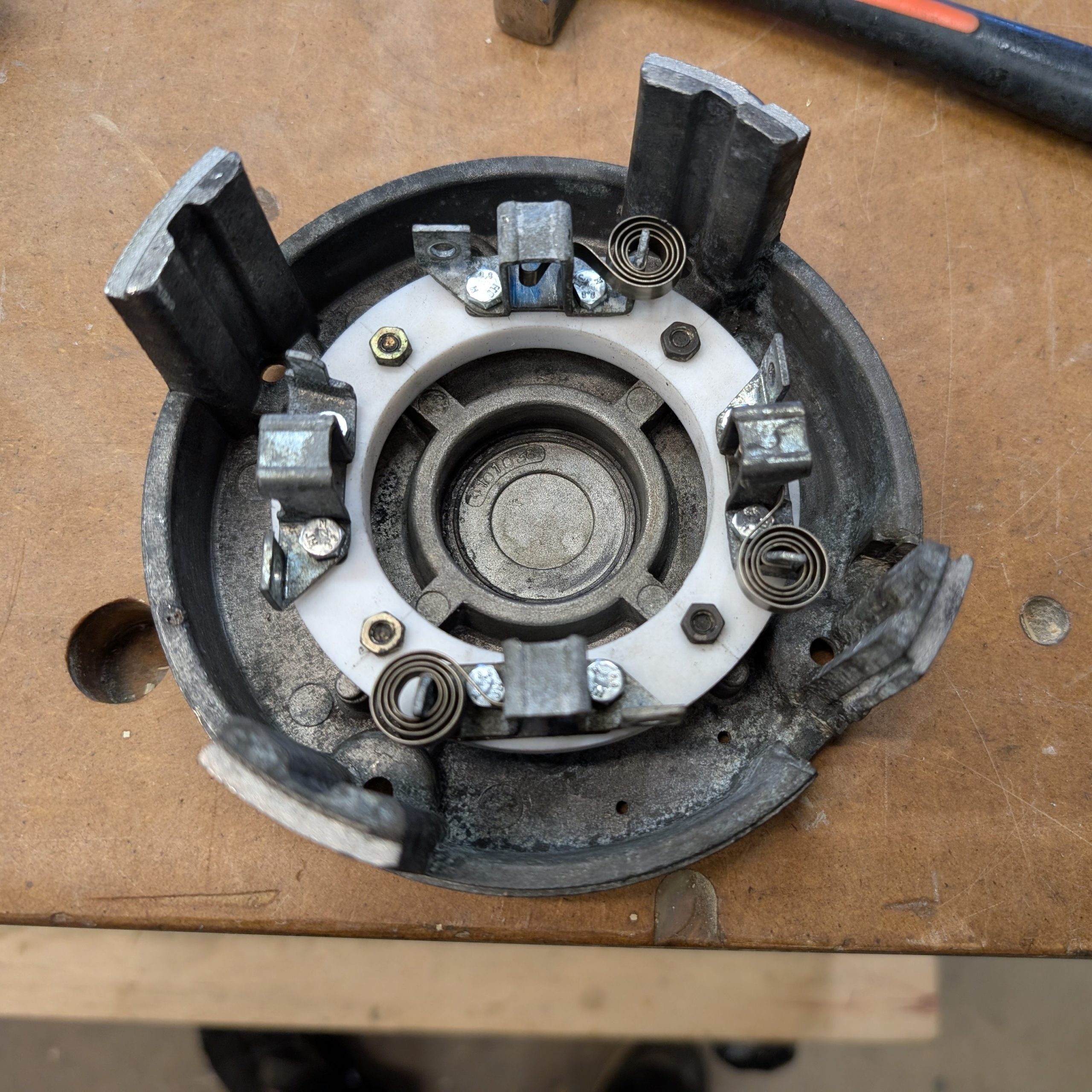

The moped features hydraulic disk brakes on all wheels. Seems reasonable on a 200 kg vehicle. Unfortunately all the brakes were stuck.

The three calipers seems pretty unique, made out of machined aluminum with a steel piston. These parts were more or less united in rust and oxidized aluminum and required extensive cleaning and brushing. The nuts for bleeding out air were bad too, one resulted in the threads in the caliper being stripped. In the end, it was possible to clean up the calipers, get the piston moving and replacing the bleeding nuts.

As for the brake lines, these were corroded but all but one hose could be kept. The last one was replaced by a custom-made hose.

Next up were the brake cylinders. The brake system consists of two separate circuits (front and back). Each one powered by an expensive Brembo motorcycle brake cylinder. These were also in bad shape but after disassembly and cleaning they seem to hold up.

New brake fluid, letting the air out and the moped is all of a sudden stoppable!

Fixing the Electrics

With battery and brakes in place, it was getting closer to actually riding the moped. Before that, the problems with the electric system needed to be fixed.

Starting with the pedal box, I found new ones (Curtis, expensive) and Chinese copies. To save money I ended up repairing the existing one. A good clean-up and a modified new potentiometer got it back to life. It even got some new paint.

All micro switches were swapped for new ones, including the brake light switch. I also found out that the 24 V connection to the DC-DC converter was bad. Fixing this got the lights more stable. The final fix for the lights was cleaning all the oxidized switches in on the handle bar.

The horn was completely rusted up so it was replaced with a new Hella horn. Pretty loud.

Head Light

The head light is a standard Hella with a H4 bulb. Only the low beam is used (there is no way to turn on the high beam). When messing around in the electronics box, some of the plastics holding the bulb in the reflector broke. Seems like it hasn’t aged well.

Some thin sheet aluminum and epoxy glue seems to have solved the loose bulb.

Turn Signals

Both of the rear turn signals were broken. These were of a stiff plastic model, probably easily broken off if hit. Spending too many hours on the web trying to find something nice to replace these, I ran into the actual model used. These are standard turn signals from the British company Vicma.

Of course I ordered a pair and mounted these. I’m pretty sure they will break, they are very stiff and are not protected at all.

First Ride

Actually all things went pretty well. After fixing all the stuff mentioned, the moped is “street legal”. It is not fully clear what kind of classification the vehicle falls into in Sweden but because no model from TransportEL has been faster than 25 km/h, it should be a “Klass 2” moped. This means it can be run on bike lanes (unless explicitly disallowed).

At this point it became clear that the moped had a chain gear ratio for a max speed of 15 km/h. What a bummer. It turns out the model was available with two different ratios and mine had the slower one!

Gears and Chain

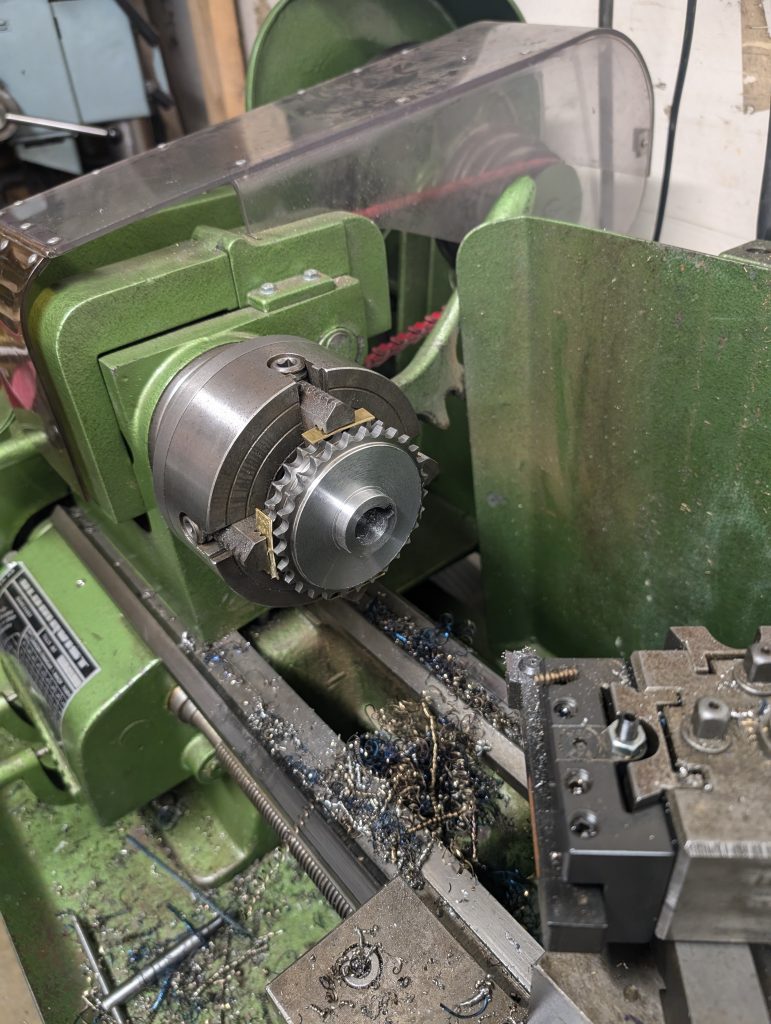

The quickest way to get to 25 km/h would have been to change the front and rear chain gears. These can still be ordered from the manufacturer, at great expense. Instead I created a spreadsheet calculating different alternatives. The cheapest solution would be to swap the front gear from 15 to 29 teeth. These gears are not of any standard dimensions so I had to order a blank Z29 gear and machine it to dimension in my metal lathe. The trickiest part was to get the inner key slot in place.

This was also a good time to replace the chain with a new one. The swap and installation of the new gear went well. Now I had a moped that reached a speed of 30 km/h under ideal conditions!

New Problems

The moped was used during the next few months, going to the supermarket, picking up parcels and moving things in the garden. A quite fun and useful toy, though being somewhat weak and slow.

Then one evening when my kids came back after a ride on the dust roads the moped spelled really bad and the motor stuttered. The smell was the one of too hot metal and electronics.

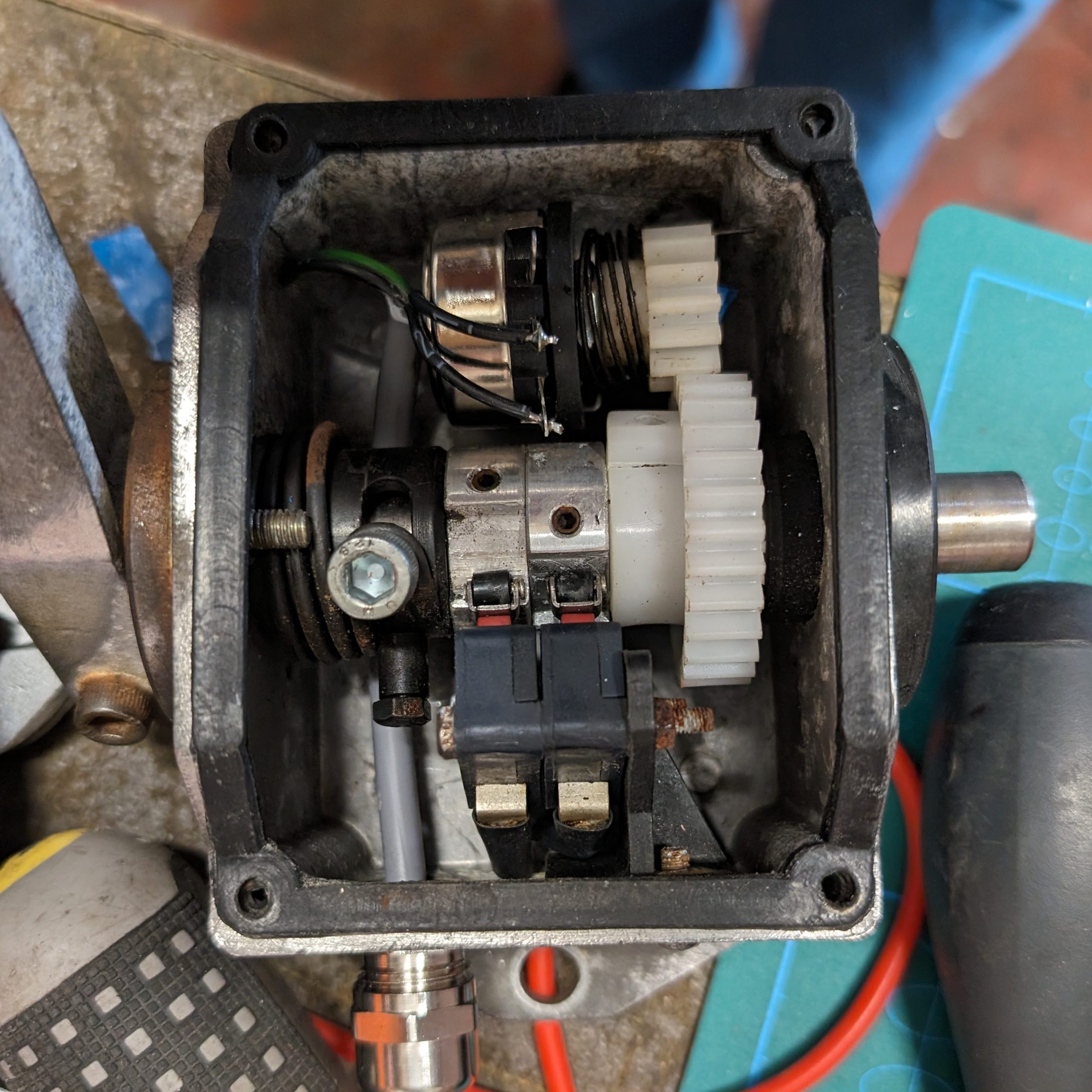

I let it cool down and next day it didn’t run at all. Removing the motor it became apparent that the carbon brushes had overheated, resulting in plastic isolators melting. This in turn had displaced the brushes and short-circuiting. It looked pretty bad.

The plastic isolator, a ring holding the brushes in place, could be replaced with something home made. Unfortunately, the brushes were damaged and two springs had partly vaporized.

A spare motor from the moped manufacturer was out of the question, the motor manufacturer didn’t answer any inquiries. I had to turn to the web to find a solution. Either to find an identical motor or something similar. This was maybe the time to upgrade the motor to get some more power?

No. It didn’t turn out that way. I found a spare motor from the same manufacturer (but lower speced) and took the chance that the brushes would look the same (they did). It wasn’t cheap but it brought the moped back to life. As a side-note, the donor motor came from a retired scrubber. I also took the opportunity to clean up the commutator and replace the motor ball bearings.

My conclusion of the cause of the overheat was that the motor commutator was oxidized resulting in high resistance to the brushes. This in turn building up heat when running the motor for a long time.

The motor is actually equipped with a bi-metal thermostat that should shut it down if too hot. When testing the thermostat, it didn’t work. I replaced it with a new, speced at a lower temperature to avoid this disaster in the future.

Adding New Bed With Walls

When I bought the moped, the bed was just an aged sheet of plywood. Usually cargo mopeds have some kind of low sides to keep things in place on the bed. Because of its previous life as a vehicle for post delivery, the bed has been covered with some kind of box with lids which is now gone. The simple sheet of plywood was probably what the next owner found easiest.

My plan from the beginning was to weld something, preferably with removable wooden sides. I wanted it sturdy and I wanted it to be galvanized. It also needed to be foldable for easy access to the battery and the electronics.

So I made some simple drawings to get an idea of the weight and material requirements. Idea was to add hinges (the ones from the plywood solution was not good at all) and reuse the old sliding locks.

I got some square tubing and sheet material and got to work. The welding took a few hours, the result was decent. All welding was done outdoors using a Kemppi MMA (stick) welder. The tubing was cut using a cheap metal chop saw that really has done it’s job for many years.

I used ordinary barrel hinges but used one left hinge and one right to get the bed frame locked in place. The tacking of the frame was done with the tube pieces clamped to the moped frame, thus getting a great fit. A final touch was a gas spring to keep the new frame in place when folded up.

The frame was then galvanized. I ran into one problem with this. I shipped the hinges too, and the holes and threads were a PITA to get useful again.

After mounting the frame, some nice fir planks were dimensioned to fit nicely into the corner pillar slots. As for the bed, I flipped the old plywood sheet and cut it to dimensions. Someday it will be replaced with a new one.

As you can see, I also added four rings on the bed to be used for cargo lashing.

I’m very satisfied with the end result of the bed. the only thing I regret is that I didn’t think of some kind of welded-in locking solution. It would have been nice to lock the bed (with a key) to make access to battery and electronics harder.

More Motor Troubles

The bed was finished at the end of the summer. During the autumn we used the moped a couple of times a week but started noticing that the motor sometimes stuttered and lost power.

I was quite worried that it would break down again and teared it down. Noticed that the carbon brushes didn’t slide well in their holders. This was an obvious cause to bad contact between the brushes and the commutator. The solution was easy, just sand the brushes a tiny bit with some emery cloth.

That helped. For some months. Then the stuttering came back ending with a motor that didn’t run at all. Sigh. Disassembling the motor confirmed what I had feared, the brushes had overheated again. Fortunately, this time there were less damage to brushes, and springs.

With a new motor setup at the horizon (more on this later), I just wanted to get the moped usable again. The solution was to make a new plastic ring to hold the brushes. Even though the original ring had quite some features, they were strictly not necessary. A new one could be made on the lathe, the holes drilled with a drill press after laying them out using a paper template.

Said and done, I chose to use PTFE (Teflon) for this. It seems to be one of the more temperature tolerant plastics. Got a small square sheet piece from Amazon and put it in the lathe.

Pretty happy with the end result.

A quick solution was to add some forced cooling (there are no fan blades or anything on the motor). The fans are mounted in a 3D-printed bracket than snaps into one of the openings over the brushes. I made closed covers for two more openings to unsure the air from the fans are forced over the brushes. The effect of the fans hasn’t been verified yet but I cross my fingers.

The Future

From now on, new projects will be posted as separate posts. I promise there are already material for a few ones.